The concept of data provenance in scientific research has grown in prevalence since the early 2000’s. To what do we attribute this increase? And more importantly, what do we mean when we say provenance, and how does its increasing importance impact life science researchers?

My first exposure to the term provenance came from the art world, where provenance as a term is quite common, especially among collectors and museums. In brief, the provenance of an artwork documents the history of ownership of a work, and can make all the difference in verifying that something is, for example, a real Matisse, or that it wasn’t stolen. An artwork with poor provenance, regardless of how wonderful, rare, or beautiful, simply doesn’t have the same value as something where provenance is unimpeachable.

The extension of the term provenance into the scientific world has had varying dimensions. There’s a direct parallel to the art world in some instances, which takes the form of a computer science problem: From where did data originate? What’s the original database, and what versions of that database have emerged since the original database’s creation?

More commonly though in recent years has been another use of the term provenance as it applies to scientific data, namely in terms of describing the evolution of data throughout a project. This narrative of how data originated and evolved, ultimately resulting in a new insight, has always been of the utmost importance. Only recently, however, has access to this whole story become virtually a requirement for understanding new scientific insights, and the provenance of data has even greater value when that data is shared and potentially reused for the purposes of another analytical pipeline. Simply stating, “we had a hypothesis, and here’s our conclusion” and including a methods section in the paper is increasingly insufficient in today’s scientific world. As a result, scientists are paying far greater attention not only to recording relevant metadata for the data they produce through experiments and analyses, but finding tools for communicating the role played by the data in the whole story, and in turn providing essential context needed for reproducibility and reuse.

Provenance’s role in ensuring reproducibility and verifiability

Quite simply, it’s hard to evaluate a priori the quality of a piece of data. Seeing its lineage, or all the data that came before it and after it in a project, allows others to verify the correctness of the data, and therefore enables trust and confidence in that data. This idea certainly isn’t new, and is perhaps is as old as science itself. Fundamentally, scientists hypothesize, experiment, analyze, and draw conclusions from their observations. And the strength of that conclusion is based entirely on whether or not the story of how that conclusion came about meets the requirements of the scientific process. For much of the history of science, a great deal of the data behind the project couldn’t be shared because it lived in the scientist’s notebook, which for centuries was the home of the project’s provenance. Nonetheless, based on the papers in which conclusions were communicated, most conclusions satisfied the requirements of reproducibility and verifiability.

That has changed in recent years. The pace of science has increased dramatically, and the rewards for repeating experiments are few. Most rely on looks alone, as communicated in the methods section of a paper. This has become harder and harder though–data has become much more difficult to collect and organize, and for a great deal of scientific research now the volume of data is significant, collected across many more analysis steps. Independent of communicating the story that led to a conclusion, researchers have begun to struggle with keeping track of the lineage and provenance of data because there are so many files, so many systems, and so many analysis steps. As a community looking from outside and simply reading a paper, it’s almost impossible to describe the process well enough for someone to repeat it independently. Researchers are yearning for the ability to look at not just the data, but the provenance of that data as a way of evaluating the merit of the story.

The Growth of Recording Provenance

Some scientific fields have led the way in communicating data provenance, largely because the analyses and exact details were so crucial to the interpretation of the results. Fields like genomics, bioinformatics, and functional neuroimaging especially have had to address these issues, and have pioneered strategies for clear data provenance, without which an outsider would be unable to evaluate a scientific project’s story. Details of the analyses that took a researcher from raw data (which is largely uninterpretable) to a conclusion are critical for understanding the validity of the conclusion. Yet many fields of science haven’t had to grapple with issues of provenance. Nonetheless, they have many of the same problems and challenges: struggling with a perceived lack of reproducibility of their experiments, the explosion of data they can collect, the complexity of their analyses, and the size of their collaborative teams. So while specialized communities have begun to create a provenance infrastructure for communicating results, a more general infrastructure that empowers researchers throughout the scientific field has only recently begun to emerge.

Importance of Tools, Technology, and Storytelling

The abundance of data and the complexity of analyses make technology essential, not only for computing results, but for managing and organizing data. Otherwise, the mundane tasks of metadata and provenance capture, along with more general data management, demands the cognitive effort of researchers that’s better spent on actually conducting scientific research. Human beings have a limited capacity to think creatively every day, so it’s essential that technology helps relieve the cognitive load of communicating scientific process. Additionally, technology can provide a framework and structure to articulate science in the way we all understand it best: through storytelling. Putting our knowledge in the context of stories and how questions and data evolved is the most effective way to transmit knowledge. This is essential not only for communication, but for creative work in the lab, as anyone who tried to bring creativity to a mass of raw data can attest. Creativity doesn’t happen in a vacuum but in context, and in science, that context is provenance.

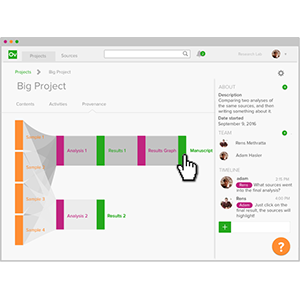

Since its start, Ovation has provided tools to researchers in the life sciences to not only organize and manage their data, but tell the stories behind their conclusions. We’d love to hear about your challenges with data provenance and your approach to dealing with it, so find us on twitter at @ovation_io or send us an email at info@ovation.io.